By Sharon Simonson

Tech companies releasing demographic data about their workforces are entering an emerging and potentially fraught conversation, though perhaps not at all about what they imagine.

Since the end of May, Silicon Valley’s Google Inc., Yahoo Inc., LinkedIn Corp. and Menlo Park’s Facebook Inc. have released “diversity” counts by gender, race and ethnicity about their national and global workers. They have uniformly criticized themselves for their largely white and Asian male populations and pledged to broaden their human spectrum.

But in their information releases — in particular their graphical representations of their workforces’ statistical makeup — the companies have used nomenclature that differs from that used by the federal government, conflating two historically separate categories: race and ethnicity.

The companies may simply embrace less specialized, more popular definitions of the terms. But in so doing, they point to the muddy public understanding of how the federal government classifies the American population for purposes including Congressional-district boundaries and the distribution of hundreds of millions of dollars in federal aid.

The companies’ methods also foreshadow contemplated change in federal policy prompted by the ethnicity-race confusion. The changes could make the 2020 census data some of the richest ever in terms of Americans’ race, ethnicity and cultural origins, opening new opportunities for self-identification to whites and blacks and expanded opportunities for others.

William Frey, a demographer and senior fellow at The Brookings Institution, said most people who are not specialists accept the words ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’ as synonymous. “Both ‘ethnicity’ and ‘race’ signal to a lot of everyday people, ‘This is your cultural heritage.’ Race used to be strictly skin color, but that has changed over time.”

The federal Office of Management and Budget is more picayune. OMB sets standards for federal data classification for all of the federal government, including the U.S. Census Bureau. According to the OMB, race and ethnicity are social and political structures that are not anthropologically or scientifically based, and they are not the same. The government began defining race and ethnicity to ensure uniformity and common understanding in federal records in response to the need to enforce civil rights. Today, the OMB definitions have broad impact and applications, extending to the workplace, medical records, and documents such as mortgage applications and school records.

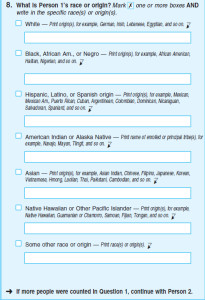

On the 2010 Census, two questions prompted Americans to define themselves in two ways: the first by ethnicity and the second by race. The form exhorted people to answer both questions.

For ethnicity or “origin,” Americans could identify themselves as “non-Hispanic or Latino; Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano; Puerto Rican; Cuban;” or “another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.” Respondents could also write an answer, with Census examples such as Argentinean, Colombian and Dominican.

For race, Americans could signify that they were multiracial (first allowed in 2000) or select from multiple race categories, including white; black, African American or Negro; and American Indian or Alaska Native. In addition the form lists six Asian subtypes (Indian, Chinese, Japanese, etc.) and offers a seventh place for Asians to write origins that are not listed, including Laotian, Thai and Pakistani. It also lists three types of Pacific Islanders and gives space for additional write-ins. (The bureau proposes to remove the word “Negro” from the black race category in 2020 too, saying its relevancy within the population is shrinking and that some people find it offensive.)

The construct — for obvious reasons — has sewn confusion, particularly among Hispanics. As a consequence millions of people— mostly Hispanics — have started selecting “some other race” when presented with the current race categories.

That non-responsiveness has troubled the Census Bureau. The bureau’s role is not to dictate to Americans their race and ethnicity, but to reflect what Americans believe themselves to be, former Census Director Robert Groves said in 2012. That means offering choices that “match what people think about their (own) race and ethnicity,” he said.

Groves’ comments summarized years of bureau research, including surveys sent to nearly 500,000 U.S. households and 67 focus-group meetings with 800 people in 26 cities including Anchorage, Honolulu and San Juan. Besides confusion among Hispanics, the bureau found people of Middle Eastern and North African descent felt they were not represented among the 2010 racial or ethnic categories. They also found that blacks and whites wanted opportunity to detail ethnic or origin information, just as Asians and Hispanics have.

The current consideration to address these shortcomings would be a break from the two-question race-and-ethnicity format to a combined race and ethnicity question, which for the first time prompts all racial groups including blacks and whites to provide detailed ethnic or “origin” information. Census examples for white “origins” include German, Irish and Lebanese; examples for blacks include Haitian and Nigerian.

Early Census Bureau research on responses to a new, combined race-ethnicity question showed that up to half of people who identified themselves as white gave additional detail when provided a write-in line and more than 76 percent of black respondents did. In addition, the number of people who resorted to “some other race,” plummeted to less than 1 percent from more than 7 percent under the two-question format of the past.

None of the Silicon Valley technology companies responded to a request for information on why they approached the disclosures as they did. Maybe public discussion of race and ethnicity prompted by preparation for Census 2020 will create new and better language tools for improved understanding.