By Sharon Simonson

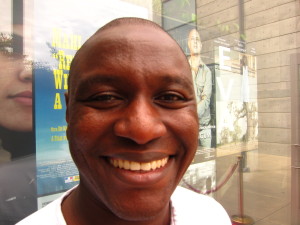

MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif. — When you set out to change the world—or just to start a new business—it helps to have “some audacity about you,” Fiifi Deku advises.

It’s true, agreed Nneka Uzoh and Uzo Amaka. “You have to have passion,” Uzoh explains, “because you are going to hear, ‘No,’ more times.”

“One thing I say to myself often: it’s another human being who told me no. Unless it is impossible, I think that I can do it,” Amaka counsels.

The trio, entrepreneurs with one foot in the United States and the other in Africa, dispense their hard-earned wisdom at the first annual Innovate Africa Forum. The event at the Community School of Music and Arts in Mountain View is a new addition to the six-year-old Silicon Valley African Film Festival, founded by the day’s master of ceremonies, Chike Nwoffiah.

Deku, a Ghana native and senior business analyst at San Jose-based Cisco Systems Inc., is building a pan-Africa news platform to feature African writers telling the African story. “We want to show the rest of the world what Africa is about and what black people are about in our own light,” he says. “This platform is going after the gap between Africans and African-Americans. We should be hungry for information about each other.”

Uzoh, who holds a master’s degree from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., is a brand spokesperson for My Muse Dolls, a toy company founded in 2013 by four African-American women—including her sister—to allow girls of color to choose their dolly’s skin tone, hairstyle and attire. It made its first sale this fall. “We are really focused on the idea of social change through dolls,” says Uzoh, who grew up with Nigerian-born parents in San Jose.

Amaka is a registered nurse, real estate broker and first-time author, there to present her autobiographical book, “Ages of Suffocation: Remembered Dreams,” a story of her early childhood in Nigeria after being kidnapped by her Nigerian father. Her mother is American.

Attendees in the 200-seat Tateuchi Hall include a dozen or so young men enrolled in the Oriki Theater Co.’s Rites of Passage program for teenage African-American boys. It is based on traditional African coming-of-age ceremonies. “This is their journey to manhood,” Nwoffiah says. “The kinds of things they are hearing you all say are so right on.”

A woman in the back row stands. “This learning that is taking place is not easy to come by,” she announces. She then explains that folks can buy a Muse doll that day. “One of them is supposed to be up for auction for this event,” she says, “and three of them for $69 each are for sale.”![]()

Fofo Gavua, a 27-year-old filmmaker from Toronto of Ghanaian descent, recounts a childhood story of his mother traveling to a neighboring Canadian state to find a black doll for his sister. When he later lived in Ghana for 14 years, he realized that the black dolls scared the other children—a useful discovery for a kid who enjoyed the occasional tease, he admits with a smile. “All of the dolls they had were Caucasian,” he says. “They were terrified of their own image.”

“I think what you are doing is really, really powerful,” he tells Uzoh.

Social media have changed the outlook and prospects for black people worldwide, Amaka says, allowing new opportunities to connect and unify. As someone who is “literally African-American,” she has often felt herself labeled as American when she is in Nigeria and as Nigerian when she is in America. As a teenager in an American high school in the early 1990s, she suffered horrible teasing.

“It took me a while to realize it was only from black girls,” she says. “It was very unsettling.” But YouTube and Facebook allow community not available 25 years ago, to everyone’s benefit. “We are trying to uplift each other,” she says.

An older white man seated near the front of the hall stands to speak. “I have problems understanding my own culture,” he says.

“That book told the story of some of the things that I also went through, but you can’t talk about,” an older woman, also addressing Amaka, says. “That book really helped me and helped me to heal.”![]()