By Sharon Simonson

SAN JOSE—Even as nativist opposition to immigration roils national political discourse, in dozens of American communities nationwide the foreign-born are emerging as heroes of local economies.

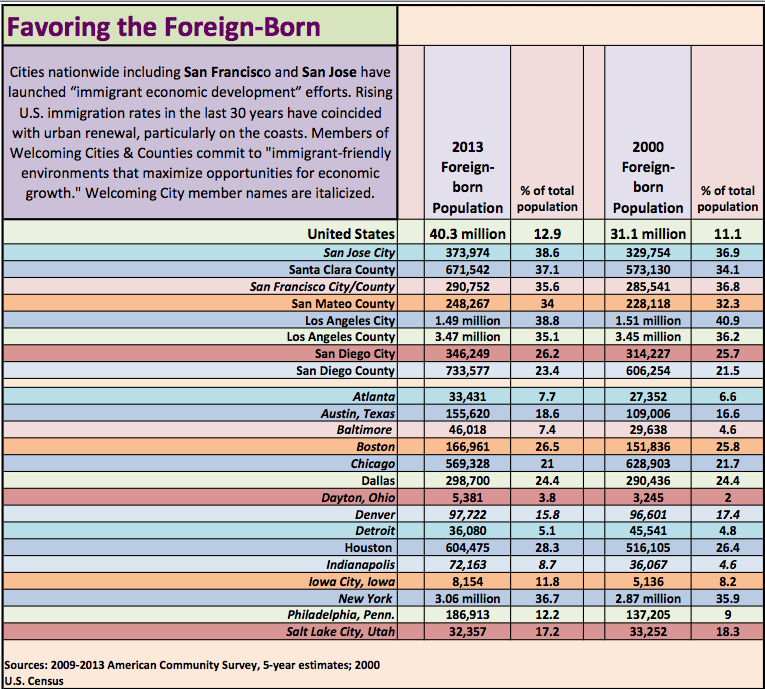

In historic immigrant gateways including the Bay Area, Los Angeles, New York City and Chicago as well as less traditional immigrant entry-points from Atlanta, Ga., to Denver, Colo., cities, mayors and other local leaders are targeting the foreign-born with new offices and resources.

In Rust Belt cities from Detroit to Cleveland to Pittsburgh, Penn., advocates are calling the movement “immigrant economic development” and touting immigration as a solution to declining populations and unstable economies. A 2012 study of the Saint Louis metropolitan area including 17 Missouri and Illinois counties found that low immigration rates since the 1950s were a significant cause of anemic population growth and the declining economy. The research precipitated the St. Louis Mosaic Project to attract new immigrants.

Foreign-born workers have become increasingly critical to Silicon Valley and the Bay Area economy too. Without new immigrants, Santa Clara County’s population would have grown 40 percent of what it did from 2010 to 2014. Immigrants accounted for 65 percent of San Francisco’s population growth in the same time.

Seventy percent of the software developers working in San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa Clara counties in 2013 were foreign-born, according to the Silicon Valley Competitiveness and Innovation Project. Fifty-six percent of those working in science, mathematics, engineering and technology-related fields were born outside the United States.

“It is not humanitarian,” said Adrienne Pon, executive director of the San Francisco Office of Civic Engagement & Immigrant Affairs of the city’s emphasis on meeting the needs of its foreign-born. The city allocates $4.5 million a year to her office.

“San Francisco is over one-third immigrant today. Immigrants own and operate over 35 percent of our small businesses. Our mayor is the son of immigrants, and several members of the board of supervisors are immigrants or sons or daughters of immigrants,” she said. The city also tracks U.S. Census projections for the country’s future workforce. “It is largely going to be people of color and immigrants. We are paying attention to that now,” Pon said.

This summer, San Francisco and San Jose became the 16th and 18th cities to join the Cities for Citizenship Initiative. C4C, launched in September 2014 by the mayors of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, seeks to promote citizenship for the 8.8 million legal permanent residents (“green-card” holders) living in the United States and eligible to become citizens. Naturalized immigrants earn up to 11 percent more than non-citizen immigrants, according to research for Cities for Citizenship. Others member cities include Milwaukee, Wis.; Philadelphia; Boston; and Chattanooga, Tenn.![]()

Not quite 40 percent of San Jose residents are foreign-born, up from 34 percent during the dot-com boom. Slightly more than half of San Jose’s foreign-born are naturalized.

San Jose’s Office of Immigrant Affairs is nascent, approved by the city council earlier this year. The city manager’s office is assembling a 15-member steering committee and multiple subcommittees to help produce an “immigrant integration plan” that it expects to present to city council in April, said Zulma Maciel, an assistant to the city manager who is leading the initiative. Committee members come from other local governments, non-profits and faith-based organizations that work with immigrants, and private enterprises including business organizations that cater to immigrant-owned businesses.

The “Welcoming San Jose Plan,” its working title, is supposed to set a high-level strategy for the city to become more immigrant friendly based on what steering committee members learn and report about what immigrants need to be successful workers, business owners, parents, spouses, students—residents of San Jose. “Where do we aspire to go? What do we aspire to be as a city?” Maciel said. “Then down the road, it’s more operational and tactical.”

She also hopes the steering committee can identify sources of financial support to do the work to implement the integration plan. “I think there are opportunities for public-private partnerships,” Maciel said. “There are big corporations in our region that hire a lot of foreign-born employees, and I would imagine they would see the value in investing in making this a more immigrant-friendly community. They are helping their employees stay.”

Demographer John Pitkin believes it is possible for U.S. cities or regions to gain the attention of immigrants and to pull them their way. The consulting demographer affiliated with the University of Southern California ties U.S. immigration rates in the last 65 years to large-scale, national settlement patterns and economic ebbs and flows. Beyond the well-known middle-class flight to the suburbs during the mid-20th century, a drop in U.S. immigration rates also accompanied the hollowing of center cities, he notes. Since immigration has increased in the last 30 years, urban areas in cities including New York and Los Angeles have recovered. Both cities have foreign-born populations nearly three times the national rate, according to the census bureau. “At the time, there wasn’t a conscious strategy of increasing immigration as a way to revitalize cities,” Pitkin said. “But can that work as a regional policy? It is reasonable to believe it can, at least in the long term.”

Immigration to the United States fell for four decades beginning in the 1930s, reaching a 20th-century low in 1970, when less than 5 percent of the population was foreign-born, according to the census. That was down from nearly 15 percent in 1910. Since 1980, immigration rates have climbed precipitously, with immigrants nearly 14 percent of the population today. Many cities across the country are engaged in massive urban renewal as residents and companies return to the centers.

The U.S. foreign-born population is headed to one in five people in the next 45 years, the census bureau predicts.

![]()